I would like to comment on the situation of Tango today (April 2023).

Concerning music, the trend that began in the late 90s and early 2000s has been increasingly affirmed, in which young musicians have revalued the relevance of dance in Tango as a whole, investigating the principles that shape the way of playing the Tango of the Golden Age, the glorious decade of the 40s, leaving aside the lines traced by

Ástor Piazzolla (see the documentary film

“Si sos brujo”).

As for the dance, the following process can be observed:

1. Firstly, in the 1980s, there was a concern about the appropriate methodology to transmit the Tango dance to everyone who wanted to learn. Let us bear in mind that for the dancers who were trained before the eclipse of Tango (for which, in my opinion, it is pertinent to take the year 1955), the way of learning to dance was what can be called “homemade” or “organic”, that is to say, they did not have to look for Tango classes, but instead, they were born in a time and an environment in which it was natural and expected of them to dance Tango. Tango was not seen as a profession, although no less was demanded regarding the quality of dance. The first steps could be taken inside the home if the relatives already danced Tango and transmitted it to the new family members along with all the other things in the home, such as meals, schedules, beliefs, and values.

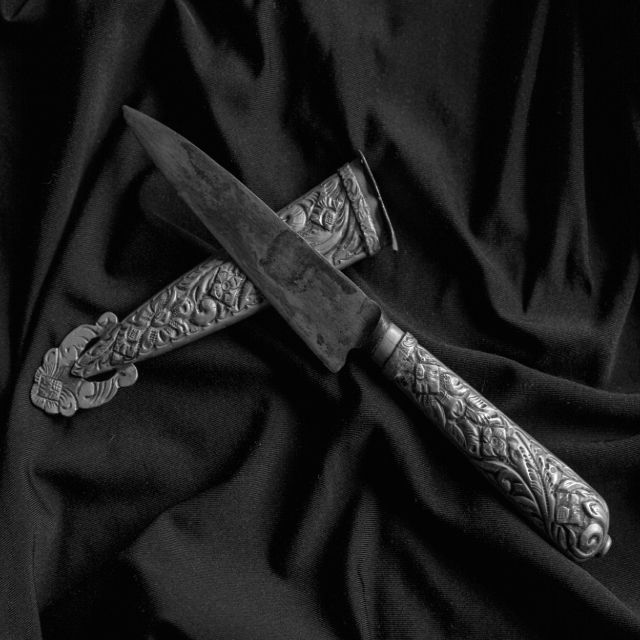

Alternatively, or in the case of starting at home, the next steps were taken not far away, with friends from the neighborhood, in the club, and in “prácticas”, which were places of research, creativity, and collective teaching, where everyone learned from everyone and those who stood out were those who could show more excellent dexterity, “mischief”, transmitted and inspired more positive emotions (love, joy, etc.) to the witnesses, who were none other than the same friends from the neighborhood who attended the same practices, or those who saw them in the neighborhood clubs once they began to participate in the milongas. Friendship, in this case, did not force them to a hypocritical acceptance and easy approval; on the contrary, it forced them to express their assessments without ambiguity, be it acceptance or rejection, which contributed to a general improvement of the dance level. In those times, there were “Tango teachers”, some more or less authentic than others, who taught the steps of Tango to those who did not belong to that more natural and homely circuit and had the purchasing power to pay for lessons. We can also find attempts (commercially successful but not in the results of good dancers), such as Domingo Gaeta, who, copying

Arthur Murray from the United States, taught to dance the Tango by mail, sending pieces of paper with foot-prints drawn, so that the student would put them on the floor and step on them and thus learn the steps of Tango.

2. The first methodology that we can find at the beginning of the “renaissance” of Tango, from the return to democracy in Argentina in 1984, is the one that uses the so-called “basic step”. This method is related to the language used in the Golden Age to communicate the necessary knowledge to dance in a more or less rational way.

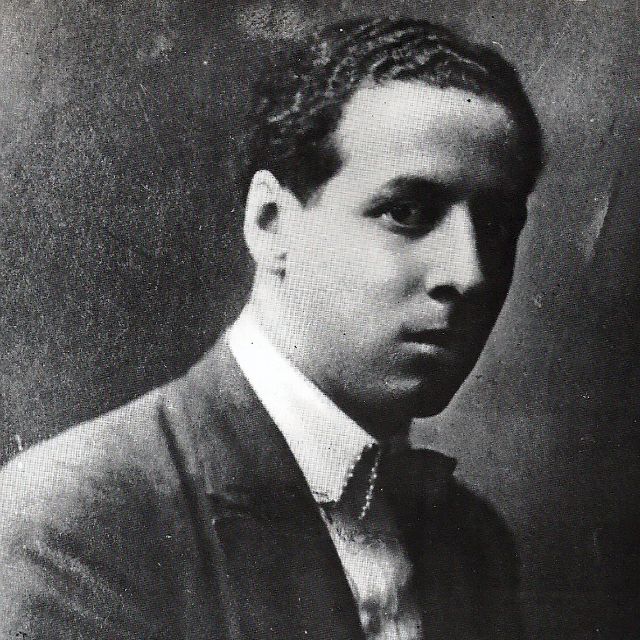

3. Then, a movement of young dancers emerged who rejected the hierarchy within the environments of the dancers who had learned in the golden age. For these dancers of the Golden Era, this hierarchy was based solely on the quality of their dance and their experience, regardless of their aesthetic choices, always emphasizing that “each dancer develops their unique style”. To dance in the milongas required a quality of dance and an experiential understanding of Tango that was very far from what the new dancers could possess and develop (let us take into account that this hiatus of almost 30 years that took place between 1955 and 1984 produced a great distance between knowledge and experience between old and new dancers). The younger and more determined new dancers, with values already different from that generation, decided to create their own spaces, methodology, and understanding of Tango, calling this movement “New Tango”. Who knew how to give a language to this new way of understanding Tango while maintaining a continuity with the Tango of the glorious era was

Rodolfo Dinzel. For Dinzel, Tango as a dance was not just “steps” but history and all the conflicts that inhabit it (social, political-economic struggles, gender conflicts, etc.) that are embodied in the dancers and continue each time that they update a choreography that does not “is” but “becomes”. However, there are very few who understood the depth of Dinzel’s vision, and much less those who today recognize his influence, the methodology that he developed to be able to explain Tango to new generations of dancers, both from Rio de la Plata and from all over the world, forever modified the physical-spiritual language of Tango, updating its interpretation to a time very different from that of the 40s and 50s.

4. Other movements arose in response to the irruption of the new Tango. Among them, the “milonguero” style that has been associated with the person of

Susana Miller, who claims to be the one who coined this name; the salon style, which was centered around a group of dancers who self-awarded the name “Villa Urquiza style” due to the geographical location of the dance halls they attended in the Buenos Aires neighborhood of the same name. Other styles can be mentioned, although the essential thing is to understand that in the glorious era of Tango, the style was something individual, and therefore, the most pertinent thing would be to make a list of outstanding dancers and couples, which I leave for another future article.

5. The appearance of the

World Tango Championship, as an attempt, conscious or not, to maintain the relevance of Buenos Aires in a

Tango that is an “intangible heritage of humanity” and its globalization, together with the faith in the economism of the predominant Anglo-Saxon culture that globalization has spread to all corners of the planet, generating two tendencies, to my understanding, equally superficial in terms of the way of assessing the significance of Tango: Tango as a profession, that is, as my grandmother Rita used to say “Por la plata baila el mono” (the monkey dances for money), in which the value of a dancer is discerned in economic terms or economic potential; hence the interest in winning a world championship is estimated in the economic benefits that this can yield in terms of publicity, prestige, and image. On the other hand, the mediocre and emotionless dance of those who dance “to distract themselves”, as a “hobby”, a superficial pastime, without caring about the quality of their dance (although there is no care for real emotions in the “professionals” either, besides acting as if they were feeling emotions while dancing for an audience). Let us remember here for a moment that those who learned to dance before the eclipse of Tango had no other interest than the personal satisfaction of being good dancers. Being good dancers coincided for them with a certain wisdom about life. Before, the objective of dancing well was to become

“the king of cabaret”; today, it is a more abstract goal: to be a “world” champion. Before, a dancer was recognized spontaneously by his peers in his community; now, he needs to be approved by the “quality control” of the judges. The evaluation system of the first case is more intrinsic, organic, and homemade, more concrete and local. In the second case, it comes more from transcendent, universal abstractions. It cannot be separated from the conditions of world capitalism, that is, money and, more specifically, the dollar, which would be something like the world champion of currencies. This particular need to appear as the ideal of dancers before the most significant possible number of people (the entire world) produces a superficialization of Tango. It is necessary to appeal to an increasingly common denominator, that is, to vulgarize it, to spread it. Thus, the most intimate and profound elements of Tango are lost. It loses its modesty. It undresses, and therefore, he empties itself. The gestures are increasingly rehearsed and therefore lose spontaneity and honesty.

As for the poetry of Tango, it is absent in a world absent of poetry. In the words of my friend and teacher, the excellent dancer and milonguero Blas Catrenau: “What can poets write about today?” “My cell phone ran out of battery, and I can’t send you a WhatsApp?” 🤣