History of Tango – Part 8: Roberto Firpo and the acceptance of the piano in the Orquesta Típica

He was born on May 10, 1884, in the City of Las Flores (today annexed to Buenos Aires as a neighborhood).

Firpo spent his childhood working in his family’s store. Although he showed interest in music and painting, his family could not afford an artistic education for him.

Since they needed his help with the family business, his father took him out of school after fifth grade.

Enrique Cadícamo tells us that, as a teenager, he felt ashamed when girls in the town watched him working hard as a delivery boy for his family business.

He confronted his father about his plan to leave Las Flores to find his destiny in the big city. Firpo displayed such determination that his father realized he could not retain him and gave him the freedom to leave home and some money to start an independent life in Buenos Aires.

He worked in a store near Santa Fe and Callao streets.

Then he worked in the shoe industry and, in 1903, at a vital steel mill, Talleres Vasena, where he met Juan “Bachicha” Deambroggio.

At the time, Bachicha was learning to play bandoneon with Alfredo Bevilacqua, one of the greats of the time, author of “Venus”, “Independencia”, “Apolo” and other classics. Firpo began assisting in these classes and learning the instrument of his choice, piano, and music theory.

Having no money to purchase a piano, Firpo made himself an instrument.

He constructed it with glass bottles filled with different amounts of water, each producing a different note, a kind of improvised xylophone, which allowed him to practice his lessons.

At 19 years old, Firpo was fiercely dedicated and learned a lot.

In 1904 he left Buenos Aires to work at the City of Ingeniero White port, where, at night, he played the piano at a bar of the port.

This allowed him to round out his training, and when he made enough money to buy his own piano, he returned to Buenos Aires and did so.

Firpo said he always remembered that day as “the happiest of his life”.

To perfect his technique, he continued his studies with Bevilacqua.

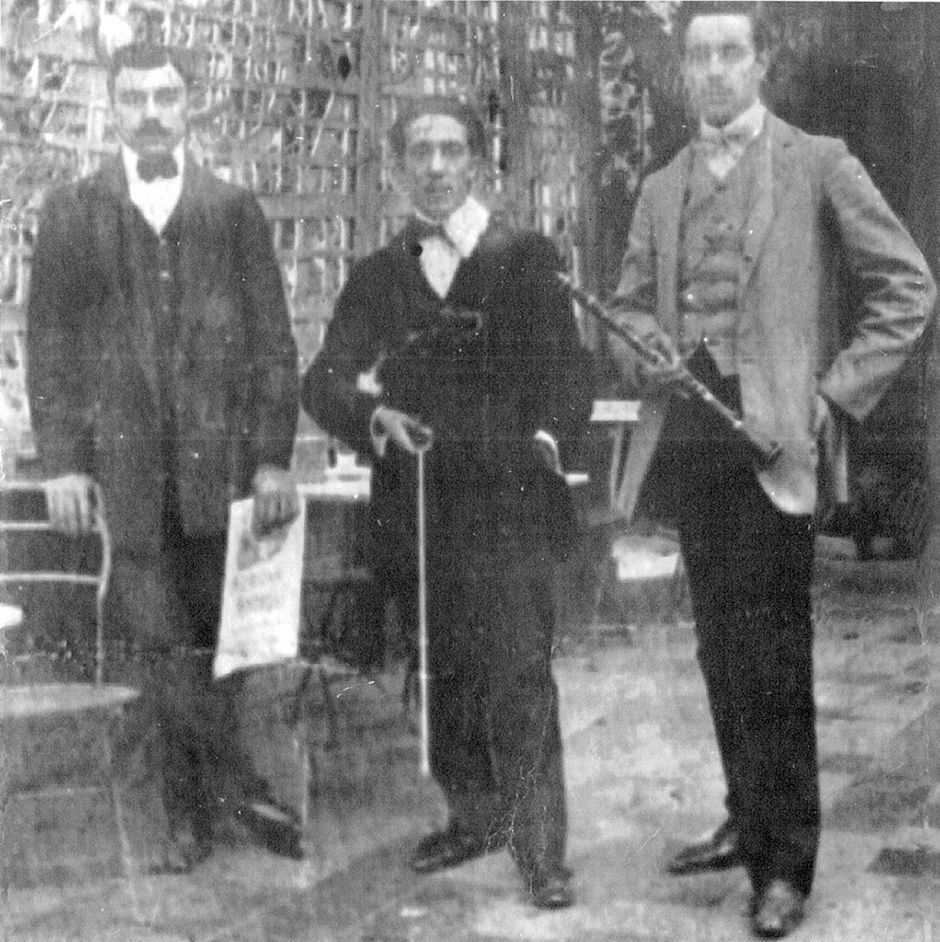

During the day, he took all sorts of odd jobs, while at night, he played in several neighborhood bars and cafés. Sometimes Firpo played in a duet with Bachicha or others in a trio with Juan Carlos Bazán on clarinet and Francisco Postiglione on violin.

In 1907, he was invited to play at La Marina, a famous place in La Boca neighborhood.

That engagement increased his fame and led to his temporary contract with another prestigious place of the tango scene, “Hansen”, in the Palermo neighborhood, at the rate of three pesos per night and permission to pass the dish (hat).

From this moment on, he worked exclusively as a musician.

During this time, he presented his first compositions: “El Compinche”, “La Chola”, and “La Gaucha Manuela” the last two would later be recorded by Pacho, adding the title of the composer to his already excellent reputation as a musician.

In 1908, with his “Trio Firpo”, he played at “Café La Castellana” on Avenida de Mayo, at “Bar Iglesias” on 1400 Corrientes Street, at “El Velódromo” and “El Tambito” in Palermo neighborhood, and at “Armenonville”, the famous cabaret.

At “El Velódromo” (a place close to Hansen), Bazán began to blow a clarinet call to attract the clientele that passed towards Hansen’s.

The result was that the latter was almost empty, while “El Velódromo” was filling up.

To solve the problem, the employer of the first contracted them again, this time for the sum of two pesos each of them!

Later, that call made by Bazán would begin his tango “La chiflada”.

In 1911, he joined the recording company ERA of Domingo Nazca, “El Gaucho Relámpago”, accompanying other musicians on his piano and recording piano solos and duets with a violin player.

Then he recorded briefly for the company Atlanta and soon moved to the recording company Odeón of Max Glücksmann.

In 1912, Firpo formed a trio with “El Tano” Genaro Espósito playing bandoneon and David Roccatagliatta on violin, performing at café “El Estribo” on Entre Rios Avenue, where Vicente Greco had performed before with Francisco Canaro. Casimiro Aín was their star dancer.

He also formed a trio with Eduardo Arolas on the bandoneon and Leopoldo Ruperto Thomson on guitar. This formation would evolve in a quartet with Roccatagliatta and into a quintet with Roque Biafore as the second bandoneon. Thomson eventually exchanged the guitar for double bass.

In 1913, while playing at Armenonville, Gardel-Razzano premiered there.

From then on, the singers would become great friends of Roberto Firpo, with whom he later worked at Odeón and toured Argentina.

On that tour in 1918, the singers abandoned him one dark night and fled to Buenos Aires to witness the revenge of Botafogo and Gray Fox in the Hippodrome of Palermo.

Recalling those days and the things that Gardel and Razzano did, Firpo said more than once: “With those jesters, you could not have peace. They drove me crazy!”

On that same night in 1913, Firpo premiered his compositions “Sentimiento Criollo”, “Argañaraz” and “Marejada”.

Firpo was at this time one of the most recognized and celebrated composers of Tango. Therefore, the recording company Lepage Odeón of Max Glücksmann summoned him to make their first recordings.

Firpo would start a catalogue of recordings on discs, only surpassed over the years by his colleague Francisco Canaro.

From the piano, he directed a set that counted on Bachicha on bandoneon, Tito Roccatagliatta on violin, and Bazán on winds.

At the time, recording the piano with other instruments presented challenges because the overwhelming sound of the piano would drown out the other instruments.

Firpo was able to resolve the problem by simply placing the instruments in an order that is still kept at the orquestas típicas.

The advantage this gave Odeón over other recording companies, in addition to his talent, is perhaps why Firpo achieved such a unique position.

Odeón was known at the time for having the best technical equipment.

Odeón hired Firpo with an exclusive contract: he would remain the only musician recording tangos with an “orquesta típica” for them.

Francisco Canaro recorded on the Era label.

Following the success of his tango “El Chamuyo”, a manager of Odeón spoke with him about recording for them. Still, since Firpo had an exclusive contract, he could block other orchestras from recording.

That is why Canaro began recording with a trio at Odeón, and sought an agreement with Firpo, “which consisted of paying him six cents for each record that was sold recorded by my orchestra” – said Canaro.

In 1914 came his most tremendous success: “Alma de bohemio”, which he composed for a play of the same name at the request of the brilliant actor Florencio Parravicini.

Other tangos by Firpo include “Fuegos Artificiales” (composed with Eduardo Arolas), “Didí”, “El Amanecer” (the first example of descriptive music in the genre), “El Rápido”, “Vea Vea”, “El Apronte”, “La Carcajada” and many others.

He was also a passionate cultivator of the waltz, from which he produced a large amount, generally with great repercussion at the time: “Pálida sombra”, “Noche calurosa”, “Ondas sonoras”, “Noches de frío” and others.

In 1916 in Montevideo, he played what would become the tango of all tangos, “La Cumparsita”, by Gerardo Hernán Matos Rodríguez, which at that time was a two-part song.

Firpo, in the style of the “Guardia Vieja”, composed the third.

Some time later he would regret not having signed it jointly: the rights of “La Cumparsita” reported millions!

Concerning this fundamental tango, Firpo recalled: “In 1916, I was at “Confiteria La Giralda” in Montevideo when one day a man arrived accompanied by about fifteen boys – all students – to tell me that they had a humble carnival march, and wanted me to take a look and fix it because they thought there was a tango.

They wanted it for that night because it was needed for a boy named Matos Rodríguez. In the score, in two by four, appeared a little of the first part, and in the second part, there was nothing.

I got a piano and remembered two tangos of mine composed in 1906 that had not succeeded: “La Gaucha Manuela” and “Curda Completa”, and I put a little of each one. At night I played it with Bachicha Deambroggio and Tito Roccatagliatta.

It was an apotheosis, and everybody celebrated Matos Rodríguez that night.

But the tango was then forgotten. Its great success began when they attached the lyrics of Enrique Maroni and Pascual Contursi”.

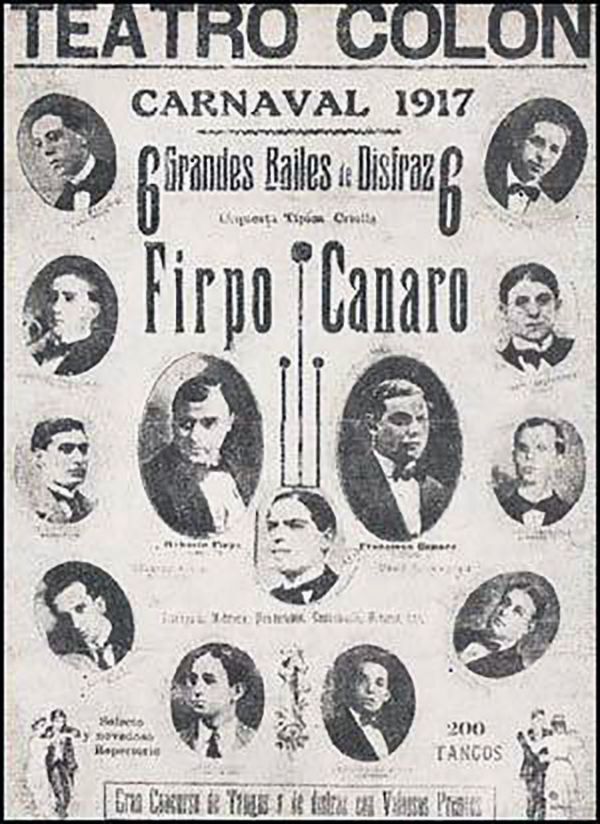

In 1917, Firpo was hired for the dance parties of the carnival at the Teatro Colón of Rosario, forming the giant orchestra Firpo-Canaro, integrated by: Roberto Firpo and José Martinez on pianos; Eduardo Arolas, Osvaldo Fresedo, Minotto Di Cicco, Pedro Polito, and Bachicha Deambrogio on bandoneons; Francisco Canaro, Agelisao Ferrazzano, Tito Roccatagliatta, Julio Doutry, and A. Scotti on violins; Alejandro Michetti on flute; Juan Carlos Bazán on clarinet; and Leopoldo Thompson on double bass.

This orchestra achieved great success, so they were hired again in 1918.

He then played with his formation in the play “Los dientes del perro”, accompanying Manolita Poli when she sang “Mi noche triste”, the lyrics that Pascual Contursiwrote for Samuel Castriota’s “Lita”, which went on to be the first tango recorded by Carlos Gardel and considered the first tango lyric structured in the way that would become classical to Tango.

On more than one occasion, Firpo shared the stage with the duet Gardel-Razzano, in addition to enduring their relentless jokes.

Once, when Firpo played the pasodoble “Que salga el toro!” (Release the bull!), at the moment in which one of the members of the orchestra shouted the title of this song in the middle of the performance, Gardel – using his index fingers as horns – struck the musicians who went to the floor.

Beyond such terrible jokes, Firpo and Gardel-Razzano recorded together once in 1917, the tango “El Moro”, although in the label, Gardel and Razzano does not appear, oddly, except – as it is – as authors. Revenge of Firpo? No. What happened is that no vocalization was planned. Gardel and Razzano just burst into the recording room, and the joke, in this case, consisted of singing the song’s lyrics, surprising Firpo. The recording company edited the record without modifying the disc label.

The success of Firpo was also financial. He made lots of money for his performances but even more for his recordings and composer’s rights.

In 1928, he unexpectedly abandoned Tango for a while.

He explained the reason to Héctor and Luis Bates: “With the money I received for the recordings, I felt like a cattleman. Everything I had, I invested in the hacienda. In a year, I got to earn a million pesos … Then came that sadly famous flood of the Paraná River that decimated my farm; I wanted to make up for so much loss, and I tried my luck in the stock market. It was in 1929. There I lost everything I had left. I had to return to the work I had done before; I formed my orchestra and started again”.

He also returned to the composition, with an eloquent title: “Honda Tristeza”.

Firpo was one of the most excellent musicians of Tango, of complete musical erudition. Nevertheless, he maintained his work within the purest traditional school.

Some of the great tango musicians who started their careers with him included Eduardo Arolas, Osvaldo Fresedo, Pedro Maffia, Bachicha, Cayetano Puglisi, Horacio Salgán, and many others.

For instance, Julio De Caro‘s first public performance and the beginning of his career playing tango was with Firpo, when De Caro was only 17 years old.

His friends arranged for De Caro to see Firpo playing at the cabaret Palais de Glace, even though De Caro was not old enough to be admitted to a cabaret.

At the time, boys would not wear long pants until they were 18 years old.

Parents would give them their “pantalones largos” as admission into adulthood.

So, Julio’s friends had to get a pair of long pants that would be the credential of being old enough to get into the cabaret, and once he was there, during Firpo’s performance, his “barra” (group of friends) started to shout “Que suba el pibe!” (Bring the boy to the stage!).

Julio joined his friends in the shouting, not knowing that “el pibe” (the boy) was him.

In short, his friends carried him onto the stage; Firpo asked his violin player to give Julio the instrument and asked him what he would like to play, to which De Caro responded, “La Cumparsita”. Eduardo Arolas was also there and was so impressed by De Caro’s playing that he asked him to play in his orchestra.

Roberto Firpo’s recording work is immense, and many titles have remained unregistered. During the time of acoustic recordings, he made more than 1650 records and, at the end of his career, back in 1959, close to 3000 recordings.

Roberto Firpo is one of the first evolutionists of Tango as a director, interpreter and composer.

In those initial days of the “Orquesta Típica”, he definitively established the piano in the tango orchestra, which displaced the guitar. Still, his way of playing the piano borrowed a lot from the way of playing the guitar in Tango and the native music of the gauchos, for instance, the “bordoneo”, a technique used to embellish the melody with notes from the sixth string of the guitar -the lowest pitched string, called “bordona”.

His orchestra was a model that pointed the way to go, signaling a trend that will germinate in future tango formations.

As a performer, he owned a very fine style – as we can hear in his exquisite solo recordings – and was the first to use the pedal, which offered a greater resonance.

As a composer, he introduced in Tango the romantic emotion, which until then was foreign to the genre.

His personality had the same magnetism as his work – tells us, again, Cadícamo.

He was always great and sweet to everybody.

Even at the peak of his fame and his fortune, he never made a display of it, always living modestly, having all that he and his family needed.

He passed away at age 85, on June 14, 1969, after being a living glory of Tango for a long time.

Read also:

- History of Tango – Part 1

- History of Tango – Part 2

- History of Tango – Part 3

- History of Tango – Part 4

- History of Tango – Part 5

- History of Tango – Part 6

- History of Tango – Part 7

Bibliography:

Internet:

- Biography by Orlando del Greco https://www.todotango.com/creadores/biografia/438/Roberto-Firpo/

- By Néstor Pinzón https://www.todotango.com/creadores/biografia/37/Roberto-Firpo/

- By José María Otero https://tangosalbardo.blogspot.com/2013/02/roberto-firpo.html

- Solo de piano por Roberto Firpo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ihrHxZTfwkU

- Primera grabación de La Cumparsita https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uK1Hjh_pM5s

- Todo Tango https://www.todotango.com/english/

- El cantor del pueblo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Jx_svJAA9s

- La Historia del Tango https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8hu2IyKjif4&t=328s

- Botellas https://youtu.be/Y1_1IiBhdsA

- La revancha Botafogo vs Grey Fox https://youtu.be/bp0MQ1otyVA

Books:

- “Crónica general del tango”, José Gobello, Editorial Fraterna, 1980.

- “El tango”, Horacio Salas, Editorial Aguilar, 1996.

- “Historia del tango – La Guardia Vieja”, Rubén Pesce, Oscar del Priore, Silvestre Byron, Editorial Corregidor 1977.

- “El tango, el gaucho y Buenos Aires”, Carlos Troncaro, Editorial Argenta, 2009.

Listen to this article:

Watch video:

Latest Spotify playlist: