Exploring the Soul of Tango: Lyrics and Dance in the Dance of Passion

Exploring the Soul of Tango: Lyrics and Dance in the Dance of Passion

This article marks the beginning of a series on the lyrics of Tango.

I wish to dedicate it to my brother, Carlos Daniel Solís, who recently passed away on April 28, 2024, at the age of 56. May he rest in peace.

Initially, it is crucial to discuss whether understanding the lyrics of Tango is necessary to dance it properly.

It’s important to note that Tango composers have always made a great effort to fuse the lyrics with the melody adequately. A clear example is Enrique Santos Discépolo, known for his meticulousness and who could spend years perfecting a single Tango.

Therefore, we can conclude that the music of Tango aims to resonate with the emotions already expressed in its lyrics and vice versa.

This indicates that understanding every word is not indispensable to feeling its emotional impact. When dancing a tango, we generally do not focus on the lyrics, as it is complicated to pay attention to both the poetry and the technical and emotional elements of the dance simultaneously.

Therefore, if our interest is to delve deeper into the poetry of lyrics, the ideal would be to listen to the tango without dancing. However, knowing the lyrics of a tango before dancing can significantly enrich the interpretation of the dance, not only for that particular tango but also by contributing to our understanding of Tango as a way to appreciate human life, estimating our existence from the assessments of the personalities who lived and were an integral part of this phenomenon called Tango, which had its peak in the 1940s in the Rio de la Plata.

Tango lyrics often reflect the repercussions of pursuing our most extreme desires, warning us about the possible consequences of this exuberant enterprise. From an involved yet distant perspective, like that of a milonga DJ from his booth, they juxtapose feelings of nostalgia and sadness with the lively excitement experienced on the dance floor. These lyrics also explore the belief in a kind of collective fiction, where a community is presumed in which we value each other. This ideal attracts us partly because we fear loneliness. Through Tango, it is possible to perceive the essences and personalities of the dancers simply by observing their movements and bodies in the dance.

Dancing Tango is also an act of pride and mastery. It is not a dance for the shy or guilty; it is not for those who wish to hide. Whoever dances Tango does not necessarily seek to be the center of attention but understands that a good dance will inevitably attract looks. This phenomenon is seen not as a quest for validation but as a gift, an offering of beauty to those spectators who know how to appreciate it without envy or resentment.

It is useful to explore the lyrics that refer to the Tango itself and its dance to deepen one’s understanding of it.

Interpretation of the tango “Que me quiten lo bailao”

Lyrics and music by Miguel Bucino, 1942, in the version of Ricardo Tanturi and his Orquesta Típica, sung by Alberto Castillo, recorded in 1943.

Listen “Que me quiten lo bailao”

“Open hand with men, and upright in any ordeal,

I have two fierce passions: the felt and the liquor…

Dancer from a good school, there is no milonga where I’m surplus,

sometimes I am poor and other times I am a lord.

What do you want me to do, brother? It’s a gift of fate!

The urge to save money has never been my virtue!

The bubbles and women’s eyes electrify me

from those sweet days of my joyful youth!

But I do not regret

those beautiful moments

that I squandered in life.

I had everything I wanted…

and even what I did not want,

the fact is that I enjoyed it.

My conduct was serene,

I was generous in good times

and in bad times, I shrank.

I was a magnate and a vagabond

and today I know the world so well

that I prefer to be this way.

What do you want me to do, brother! I was born to die poor,

with a tango between my lips and in a muddled game of cards.

I play, sing, drink, laugh… and even if I don’t have a penny left,

when the last hour strikes… let them take away what I danced!”

“Que me quiten lo bailao” is a popular phrase in Spanish that expresses the satisfaction of enjoying lived experiences, regardless of future consequences. The lyrics and music of this piece, created by Miguel Bucino, encapsulate this philosophy of life through the lens of Tango.

The lyrics could be interpreted as a celebration of the freedom and pleasure found in Tango dancing, suggesting that once lived, these experiences are inalienable, a personal treasure that cannot be taken away by external circumstances or the passage of time. In the context of Tango, this expression takes on a nuance of defiance and detachment, characteristics resonant with the genre’s emotionally intense and often melancholic nature.

Tango is an artistic expression that allows dancers and listeners to connect with deep emotions, and “Que me quiten lo bailao” serves as an anthem to live fully and without regrets. It reflects a joyful acceptance of all that life has to offer despite its inevitable ups and downs.

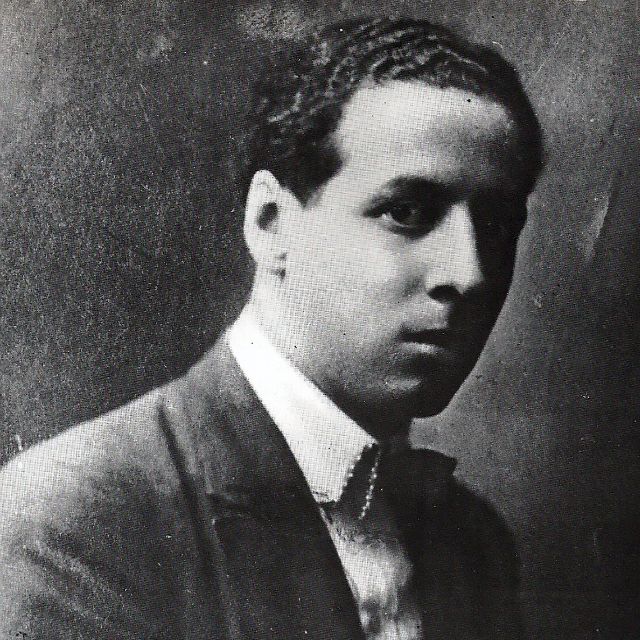

Miguel Bucino, born on August 14, 1905, in San Cristóbal, Buenos Aires, began his musical career playing the bandoneón. At 17, he briefly joined Francisco Canaro’s orchestra in 1923, which dismissed him for being a poor musician and encouraged him to pursue dancing, a vocation for which he showed natural talent. Bucino made his professional debut at the Teatro Maipo in 1925, and his career as a dancer quickly took off. He traveled with Julio De Caro to Brazil in 1927 and toured Argentina with the show “Su Majestad El Tango.” He pioneered dancing Tango at the Teatro Colón in 1929 and continued his career in Europe in 1931, performing in cities like Madrid and Paris. He participated in several theatrical seasons with figures such as Francisco Canaro and Ivo Pelay, teaching Tango to royalty and Hollywood celebrities such as the princes Humberto of Savoy and Edward of Windsor and actors Ramón Novarro and Jorge Negrete.

Although initially unsuccessful as a musician, Bucino excelled as a Tango composer, registering between 60 and 70 works, including hits like “Bailarín compadrito” and “Que me quiten lo bailao”.

Bucino retired in 1942 and died in Buenos Aires on December 15, 1973, leaving a lasting legacy in the world of Tango as a dancer, lyricist, and composer.

Here we could see him dance a tango with the celebrated actress and singer Tita Merello in the film “Noches de Buenos Aires”:

Listening to a tango means interpreting it in a personal way. Tango is felt from within. Our inner selves, with all our experiences, emotions, repressions, and more, listen to that tango, that lyric with music, and recreate it in many ways. Some interpretations become habitual and thus are maintained, becoming like translations of what is said for everyone in what we believe we hear.

Following this idea, which I believe is shared by those who love Tango, I propose a way to understand this tango, although I clarify that I do not seek to be objective or definitive.

This is what my life, my dance, hears in this tango:

The first verse, “Open hand with men, and upright in any order,” suggests a vision of masculinity based on integrity and fairness. The phrase” “open hand” can be interpreted as a symbol of generosity and transparency in relationships with other men, indicating a willingness to treat others justly and without secrecy. On the other hand “upright in any ordeal” highlights the importance of maintaining honorable conduct, regardless of the circumstances. Together, these expressions advocate for masculinity that relies on mutual trust and respect for codes of conduct that ensure equality and dignity among people without resorting to excuses based on external factors such as social position, economy, or biological or psychological conditions. In essence, it proposes an ideal of masculinity that values and promotes nobility in dealing with others, emphasizing personal responsibility over deterministic influences.

The second verse, “I have two fierce passions: the felt and the liquor” clearly illustrates the intensity and commitment with which the character lives his emotions: the cosmic chance against which we pit our will, trying to divert its course to fulfill our desires, using vital enthusiasm as a way to gauge our existence. This line highlights how the character faces that chance and uncertainty of human existence, not with fear or caution, but with an iron will to tilt events in his favor and satisfy his deep desires. The “vital enthusiasm” mentioned becomes his bulwark against mundanity and monotony, using his zest for life to measure and affirm his existence. In this context, the verse not only reflects a statement of affirmation of an orderly life from the ethical and aesthetic value of emotions but also a life philosophy that fully embraces uncertainty and enthusiasm as essential elements of human experience.

The third verse, “Dancer from a good school, there is no milonga where I’m surplus,” speaks to the technical mastery acquired through study and guided practice and reflects the respect and admiration the dancer generates within the Tango community. Essentially, the verse celebrates the achievement of excellence and elegance in dancing, which is only possible through the choice of good mentors and an unwavering commitment to continuous learning. The act of dancing and the milonga are used metaphorically to talk about life in general and how we conduct ourselves in it. Here, “dance” symbolizes how we move and react to the different rhythms and challenges that life presents us. Being a “dancer from a good school” implies having learned and mastered the skills needed to navigate these challenges with grace and competence through individual effort and determination and by choosing “good school”, that is, good guides. The “milonga”, a place where Tango is danced, represents the various situations and environments we encounter in life. Saying “There is no milonga where I’m surplus” suggests that the dancer, thanks to his preparation and skill, can adapt and excel in any context or situation that life presents, never being redundant or inadequate, but always being a valuable addition. This metaphor extends the idea that, just like a Tango dancer trained in a good school, a person who is well-prepared by their experiences and education can effectively face any life circumstance. Achievements and recognition of the dancer parallel the successes that a person can achieve in their personal and professional life when they are well-prepared and can adapt fluidly to different situations, showing that preparation, continuous learning, and adaptability are crucial to success in life, just as they are in dance.

The fourth verse, “sometimes I am poor and other times I am a lod,” reflects the acceptance of the fluctuations of fortune throughout life, recognizing how circumstances can shift between extremes of wealth and poverty. This phrase encapsulates the fact that we cannot always control the external factors that affect our economic and social position. This acceptance is not focused solely on economic reality but on a life philosophy that values other riches that are not material. The phrase indicates that the individual does not measure their worth or success solely through material wealth (“I am poor”) nor allows moments of abundance to define their identity completely (“I am a lord”). Instead, the person adapts and values life and experiences beyond material wealth. Thus, the verse suggests a balanced and mature approach to life, gracefully taking adversity and prosperity, emphasizing the importance of resilience and maintaining dignity and self-respect regardless of economic circumstances. This perspective can be compelling in contexts like Tango, where art and personal expression are often valued more than material wealth.

The fifth verse, “What do you want me to do, brother’s a gift of fate!” expresses an attitude of acceptance toward life’s circumstances beyond our control, viewing them as part of a predetermined destiny or luck that befalls us. This approach reflects a life philosophy that accepts the highs and lows with serenity and gratitude, recognizing that what happens to us, positive or negative, can be seen as a “gift of fate”. This perspective invites us to embrace life as it comes, not resisting the events but receiving them with joy and optimism. By considering events as gifts, it emphasizes the idea that every experience has inherent value, regardless of its apparent nature. This attitude fosters a sense of inner peace and satisfaction and enables facing challenges with greater strength and maintaining a cheerful disposition towards uncertainty.

In summary, this verse distills the essence of living with joyful acceptance and a calm faith that, in some way, what life brings has its purpose and value, teaching us to cherish every moment as an unexpected and often undeserved gift but always meaningful.

These discussions and analyses of Tango lyrics offer a deeper insight into how the dance and its music can serve as a profound commentary on life, personal philosophy, and social interactions, providing not just entertainment but also lessons and reflections that resonate with the emotional and philosophical depths of those who engage with it deeply. The reflections within Tango lyrics like those of “Que me quiten lo bailao” extend beyond the dance floor, weaving into the fabric of life a philosophy that values experience over material gain, personal authenticity over societal expectations, and emotional expression over restrained conformity. This resonates deeply with the Tango community and beyond, illustrating the universal themes of life’s fleeting nature, the richness of lived experiences, and the celebration of the human spirit in the face of life’s uncertainties.

Continuing with the exploration of the lyrics, the verses “But I do not regret / those beautiful moments / that I squandered in life. / I had everything I wanted… / and even what I did not want; / the fact is that I enjoyed it.”

These lines express a profound acceptance and appreciation for life’s experiences, even those that might be seen from a conservative or materialistic perspective as wasteful. This attitude rejects the notion that time should always be spent productively in an economic sense and instead celebrates the intrinsic value of experiences for the wisdom they impart.

This perspective acknowledges that life should not be judged solely by tangible, cumulative outcomes, like money or possessions, but also by moments of happiness and personal fulfillment, regardless of their “economic utility”. By stating that he does not regret those “squandered moments”, the speaker fully embraces his past and the decisions he made, viewing them as essential to his narrative and growth.

This stance also suggests generosity towards oneself and life, a willingness to live fully and unreservedly, and the recognition that each experience, however transient, enriches our being and contributes to the fullness of our existence. By freeing oneself from the pressure to justify every moment of life regarding material gain, the speaker invites us to value life for the quality of its experiences and the emotions it evokes.

“My conduct was serene, / I was generous in good times / and in bad times, I shrank.”

These lines reflect a conscious and balanced approach to the various situations of life. Here, the speaker presents himself as someone who maintains calm and serenity (“My conduct was serene”), suggesting a thoughtful and mature way of handling both times of abundance and adversity.

Being “generous in good times” indicates a willingness to share freely his resources and joys with others. This generosity is material and emotional, reflecting an openness to enjoy and share the good times fully.

On the other hand, “in bad times, I shrank,” which demonstrates a prudent and modest attitude during difficult periods. This phrase can be interpreted as reducing ostentation or expenditure, a restraint in behavior to better cope with times of scarcity or challenge. It does not necessarily imply surrendering or withdrawing completely but rather a wise adaptation to less favorable circumstances.

Together, these verses encapsulate the wisdom of living according to the circumstances, knowing when to extend oneself and when to conserve resources. The speaker understands his capacities and limitations and acts in a way that maintains a sustainable balance throughout his life. This demonstrates a life philosophy that balances generosity and caution, allowing the individual to navigate life’s highs and lows with grace and dignity.

The final lines are: “What do you want me to do, brother? I was born to die poor, / with a tango between my lips and in a muddled game of cards. / I play, sing, drink, laugh… and even if I don’t have a penny left, / when the last hour strikes… let them take away what I dance!”

These lines encapsulate a declaration of acceptance and celebration of life on the speaker’s terms, challenging social norms that value the accumulation of material wealth as an indicator of success and fulfillment.

This passage reveals a deep resignation and yet joy in the lifestyle chosen by the speaker, one that prioritizes sensory and emotional experiences—dancing, music, games, singing—as sources of wisdom, over financial security (“I was born to die poor”), not only accepts but also embraces a life free from the constraints and worries that accompany material wealth, suggesting there are a much deeper richness life’s experiences and in personal authenticity.

The verse “I play, sing, drink, laugh… and even if I don’t have a penny left” reinforces the idea that true happiness, satisfaction, and wisdom come from living fully, joyfully, and without regrets, regardless of financial status. The closing phrase “let them take away what I dance,” is a popular saying meaning that no one can take away lived experiences, emphasizing that what we truly value at the end of our days are those moments lived and the knowledge we have bestowed, not the accumulated wealth.

These verses are a hymn to a life lived with authenticity and passion, a reminder that in the end, when “the last hour strikes,” what counts are the joys, experiences, and wisdom we have gathered, not the money. According to the speaker, life is to be lived fully and with a joyful acceptance of our fate, finding beauty and meaning in art, shared experiences, and the wisdom gained rather than in material wealth.

Each moment thus becomes fully justified.

We can die at peace with our desire, having found our answer to the question of how to live.

More articles about Argentine Tango