History of Tango – Part 5: The appearance of the bandoneon in Tango

During the 1870s arrives to Buenos Aires a very particular immigrant: the bandoneon.

Tango was in its infancy, as well as this new instrument, which was recently invented in 1846 in Germany by Heinrich Band, according to some versions, or Carl F. Zimmerman, according to others. None had patented it. The bandoneon is a musical instrument that resulted from the evolution on the concertina, invented in 1839, inspired in the accordion, and conceived as a portable version of the harmonium. It is of the hand-held bellows-driven free-reed category, sometimes called squeezeboxes. The sound is produced as air flows past the vibrating reeds mounted in a frame.

Tango was in its infancy, as well as this new instrument, which was recently invented in 1846 in Germany by Heinrich Band, according to some versions, or Carl F. Zimmerman, according to others. None had patented it. The bandoneon is a musical instrument that resulted from the evolution on the concertina, invented in 1839, inspired in the accordion, and conceived as a portable version of the harmonium. It is of the hand-held bellows-driven free-reed category, sometimes called squeezeboxes. The sound is produced as air flows past the vibrating reeds mounted in a frame.

The oldest known musical instrument that uses this method is the Cheng, a “mouth organ”, already used in China on 700 AC, made of several bamboo canes (13 to 36) which had inside the vibrating membranes and a gourd as resonance box. The air flow was produced by blowing on it, like a flute.

The oldest known musical instrument that uses this method is the Cheng, a “mouth organ”, already used in China on 700 AC, made of several bamboo canes (13 to 36) which had inside the vibrating membranes and a gourd as resonance box. The air flow was produced by blowing on it, like a flute.

During the 1800s this principle of production of sound was known in Europe, from which derived many diverse instruments, some in use still today, like the harmonica, the harmonium, the accordions, and the concertinas, which is considered the immediate ancestor of the bandoneon.

Carl Friedrich Uhlig (1789-1874) created the concertina in 1839, inspired in the accordion of the Viennese Cyrill Demian (1772-1847), as an improvement of it.

The first concertina of Uhlig had 5 buttons on each side, for higher pitch notes destined to the melody on the right, and for lower pitch or basses on the left. This concertina produced 2 different notes per button, one opening, and a different one closing the instrument, obtaining in this way 20 different tones. This instrument already had the seeds of what would become one day the bandoneon of Tango.  The goal of Uhlig was to attain an instrument that, eliminating the difficulties of transportation of the harmonium, had a similar sonority that perfectly amalgamates with the string instruments, allowing its integration into the chamber music ensembles and not constraining it to the interpretation of popular music. That is why he continues improving it.

The goal of Uhlig was to attain an instrument that, eliminating the difficulties of transportation of the harmonium, had a similar sonority that perfectly amalgamates with the string instruments, allowing its integration into the chamber music ensembles and not constraining it to the interpretation of popular music. That is why he continues improving it.

In 1854 Uhlig presented his creation at the Industrial Exposition of Munich, receiving a medal of Honor.

These instruments were highly popular, although they did not have the destiny desired  by its creator, as they were mostly adopted by farmers and workers who began to execute it by ear or with a notation system using the small numbers written on each button. Later, other luthiers continued adding buttons, until it reached 62. In 1844, scientist and luthier Charles Wheatstone (1802-1875), patented the English concertina.

by its creator, as they were mostly adopted by farmers and workers who began to execute it by ear or with a notation system using the small numbers written on each button. Later, other luthiers continued adding buttons, until it reached 62. In 1844, scientist and luthier Charles Wheatstone (1802-1875), patented the English concertina.

This instrument has hexagonal resonance boxes, while in the Uhlig invention, called also German concertina, they are squared. The bandoneon derives from the German concertina. According to some versions, Carl F. Zimmerman modified Uhlig’s concertina, adding buttons and rearranging its disposition, creating what became known as “Carlsfelder concertina” (derived from the German city Carlsfeld, where Zimmerman lived and created his concertina), in opposition to “Chemnitzer concertina” (derived from the German city Chemnitz, where Uhlig lived and created his concertina).

Zimmerman later emigrated to the USA, selling his factory to Ernst Louis Arnold, another instrument maker that will be connected to the origins of the bandoneon. In 1840, Heinrich Band, a musician from Carlsfeld, gets to know Uhlig’s concertina in a visit to Chemnitz.

He really likes the instrument but fell compelled to improve it. In 1843 he opens a musical instrument shop in Carlsfeld, and in 1846 starts selling his improved version of Uhlig’s concertina with 28 buttons that play two different tones each, and a different arrangement in the disposition of the buttons. This is the instrument that began to be referred to as bandoneon, although Heinrich Band considered it a concertina, and never patented it. He later yet improved it up to produce models of 65 buttons with two different sounds each.

He also contributed to the diffusion of the instrument with several transcriptions of piano works into bandoneon and composed waltzes and polkas to be played with bandoneon, although this information contradicts another version, which states that Heinrich Band conceived his instrument to play sacred music.

Heinrich Band dies 39. His widow, Johana Sieburg, partnered with Jaques Dupon in 1860 to continue the production of bandoneons.

Heinrich Band did not make the bandoneon himself. He designed it and ordered its production from Carl F. Zimmerman.

Alfred Band, the first son of Heinrich and Johana, wrote one of the first books related to the bandoneon, with all the major and minor scales. Ernst Louis Arnold, who bought Zimmerman’s factory, will become the most prominent bandoneon producer.

His son, Alfred Arnold, who worked in the factory from his childhood, will eventually devise a bandoneon of 71 buttons of two notes each. His version, called “AA”, will become the preferred one by the Argentine Tango musicians.

There are many different versions of the concertina and the bandoneon.

There are different button arrangements, as we saw with the Carlsfelder and Chemnitzer concertinas, and in some models each buttons plays only one note.

These could become confusing, so in 1921, Emil Schimild of Leipzig proposed the unification of all the buttons’ arrangements of concertinas and bandoneons in one instrument.

This proposition did not prosper, but in 1924, it was agreed to the unification for the button’s arrangement for the bandoneon, with a model of 72 buttons producing 2 notes each (144 tones), although the model adopted by Argentine Tango musicians is one of 71 buttons (142 notes), and Alfred Arnold continued its production exclusively for them. Alfred Arnold would take orders from Argentine Tango players that asked for the inclusion of more tones, and customize them.

After the Second World War, Alfred Arnold’s factory, which was located in what became Eastern Germany, was expropriated and ended the production of bandoneons to become a diesel engine’s parts factory. Arno Arnold, Alfred’s nephew, was able to escape from Eastern Germany and opened a bandoneon production factory in Western Germany in 1950, with the aid of Alfred’s former technician, Mr. Muller.

This factory closed after Arno’s death, in 1971. Klaus Gutjahr, a bandoneon player who graduated from the Bandoneon School of Berlin University, started to build handcraft bandoneons in 1970. At the end of the 1990s, he partnered with Paul Fischer in the Paul Fischer KG Company, a musical instrument manufacturer, set about reviving the manufacture of bandoneons in conjunction with the Eibenstock municipal authorities.

The Paul Fischer KG Company, together with the Institute for the Manufacture of Musical Instruments of Zwota, developed a 142 tone bandoneon in 2001. The Bandonion and Concertina Factory Klingenthal is continuing the tradition of the legendary “AA” instruments and thereby the construction of bandoneons at Carlfeld.

The materials and construction used correspond to the legendary “AA” instruments. Using historic instruments, experiments are being carried out to test the acoustic, material, and mechanical parameters in conjunction with the Institute for the Manufacture of Musical Instruments of Zwota.

The manufacturing process has been set up using these parameters and this can be demonstrated by means of measurements.

Because the bandoneon was not patented, there is no information ever recorded about the material used for its construction, like the precise alloys of the metallic vibrating reeds, different for every note.

In Argentina, bandoneons were hand made by Humberto Bruñini, resident of Bahía Blanca. After he passed away, his daughter Olga continued with the tradition until she passed away in 2005.

The first bandoneon player ever mentioned in Buenos Aires was Tomas Moore, “el inglés” (the English man), although some said he was Irish, who brought this instrument to Argentina in 1870.

A Brazilian man called Bartolo is also mentioned as the first to bring this instrument to Buenos Aires. Ruperto “el Ciego” (the blind man) is mentioned as the first one to play tangos with his bandoneon.

He played in the proximity of the market on Moreno street for alms. Pedro Ávila and Domingo Santa Cruz (author of the famous tango “Unión Cívica”) played the concertina until Tomas Moore presented them his bandoneon.

José Santa Cruz, Domingo’s father, also switched from concertina to bandoneon. He is regarded as playing military calls with a bandoneon during Paraguay’s war, but it is most probable that at that time he played the concertina. Pablo Romero, “el pardo” o “el negro” is regarded as one of the first to play tangos with bandoneon, in the area of Palermo.

Contradictory versions mention him as either playing before or being a student of “el pardo” Sebastián Ramos Mejía.

These bandoneons were a primitive version of 32 tones. After 1880, when Tango began to develop its definitive form, the most recognized bandoneon players were:

Antonio Francisco Chiappe, born in Montevideo in 1867.

His family moved to Buenos Aires in 1870 to the neighborhood of Barracas, where he later had a butcher shop. He also was a professional cart driver, who became the president of the Association of Professional Cart Drivers.

He was a magnificent bandoneon player, who would brag of his talent posting advertisements in the newspaper, challenging to whoever wanted to bet money to who played better Waldteufel’s waltzes, although he never made his living out of playing music.

He never played in other locations than family home parties. He played with “El Pardo” Sebastián Ramos Mejía a primitive tango, or “proto-tango”, “El Queco”, very popular in his time.

He also conducted several musical formations, from which it is important to highlight one that foretells the “orquesta típica criolla” of Vicente Greco. In this orchestra, he counted with bandoneon, violin, flute, clarinet, harmonium, two guitars and bass.

According to Enrique Cadícamo, in his poem “Poema al primer bandoneonista”, the first bandoneon player of Tango is “El Pardo” Sebastián Ramos Mejía, but today is agreed the affirmation of the historian of Tango Roberto Selles that it was Antonio Chiappe.

“Vientos de principios de siglo que hicieron girar las veletas y silbaron en los pararrayos de las residencias señoriales de San Telmo, Flores y Belgrano. Entonces el Pardo Sebastián Ramos Mejía era primer bandoneón ciudadano y cochero de tranvía de la Compañía Buenos Aires y Belgrano. El pardo Sebastián inauguró un siglo con su bandoneón cuando estaba en embrión la ciudad feérica y la calle Pueyrredón era Centro América. Primer fueye que encendió la luz del Tango, en las esquinas. A su influjo don Antonio Chiappe, también bandoneonista, se dió el lujo de desafiar por medio de los diarios al que mejor ejecutara los valses de Waldteufeld, extraordinarios… El Pardo Sebastián contagió su fervor a los hermanos Santa Cruz que actuaban en el cafe Atenas de Canning y Santa Fe donde se aplaudían los tangos de Villoldo -El choclo y Yunta brava- que tanto apasionaban a Aparicio, el caudillo, y al chino Andrés. Sebastián Ramos Mejía, decano de la facultad de bandoneón, inauguraste un siglo cuando estaba en embrión la ciudad feérica y la calle Pueyrredón era Centro América.” “Poema al primer bandoneonista”, Enrique Cadícamo.

“El Pardo” Sebastián Ramos Mejía was descendent of African slaves and was “mayoral” (driver) of the tramways puled by horses, on the line Buenos Aires-Belgrano.

He played in the Cafe Atenas of Ministro inglés (today Scalabrini Ortiz) and Santa Fe. His bandoneon had 53 tones.

He is regarded as giving some bandoneon lessons to Vicente Greco.

The bandoneon was not immediately accepted by Argentine Tango musicians and dancers.

The original formations of flute, violin, and guitar played a staccato, bright and fast rhythm. The bandoneon, with its “legato”, with its low keynotes, which were favorited by its players, who would constantly insist to its German producers to add more low keynotes, seemed not belonging to Tango. But in fact, it gave Tango what Tango was missing until the integration of bandoneon, and the bandoneon found the music it seemed to be created for.

The bandoneon, contrary to other instruments of Tango, like the violin, the flute, the guitar, the harp, or later, the piano, had no traditions to refer to.

It was a blank piece of paper in which anything could be written yet. Neither it was maestros nor methods for it. Everything had to be created from scratch. Perhaps the similarities between its sound and the sound of the organitos that disseminated Tango all over helped to its acceptance (see more at Part 2).

Juan Maglio “Pacho” was essential to the acceptance of the bandoneon as a musical instrument of Tango.

Juan Maglio “Pacho” was essential to the acceptance of the bandoneon as a musical instrument of Tango.

Born in 1881, he started to learn to play bandoneon by watching his father play it every day after work.

He would pay attention to the finger positions and then practice them secretly on his home’s roof.

He went to school until the age of 12, when he started to work, first in a mechanic workshop, then as a laborer in different activities, and then in a brickyard.

At the age of 18, he decided to fully head into his vocation: music.

During the years of hard work, he kept practicing, in order to stay in shape for when the opportunity knocks.

But still, he had technical issues to resolve, like developing greater independence between right and left hands, and he went in search of instruction to the more experienced Domingo Santa Cruz.

He improved notoriously, and from his bandoneon of 35 buttons, moved successively to instruments of 45, 52, 65, 71 and at last, a customized bandoneon of 75 buttons.

His father called him “pazzo” (the Italian word for crazy) in his childhood, due to his restless character.

His friends could not pronounce this word, and called him “Pacho”.

He loved to make jokes.

If you were in the area of Maldonado creek in 1918 and saw a ghost, it was Pacho, who wandered around every night with a white bed sheet to have fun scaring the people that passed by.

He dressed with sobriety and distinction, and he insisted to his musicians to do the same.

He started playing as a professional at the beginning of the 1900s, first in brothels and then in Cafés, until, due to his rising prestige, he was convened to play at the very famous Café La Paloma, in Palermo, in 1910.

It is important to clarify that the Palermo of that time was not the same upper-class neighborhood we know today.

In those years it was an area of “compadritos”. Lots of people came to listen to Pacho there. The special rhythm of Pacho’s interpretations of tangos brought many of the best dancers of the time, like El Cachafáz, to listen, because it was not place to dance.

One night, a group of the audience from the neighborhood of Once, more upper class than Palermo, took him in litters and carry him to Café Garibotto, in San Luis and Pueyrredón.

There he later presented a quartet of the bandoneon, flute, violin, and a 7 stringed guitar. Around those years Pacho started to present his compositions: “Armenonville”, “Un copetín” and “Quasi nada”.

He attracted so many people to his concerts, that the police began to suspect that it was not only music that the Café offered to its clientele, and one night they entered abruptly and arrested everybody, clients, waiters, musicians, the owner and the cat… But they found nothing.

In response, Pacho wrote his tango”Qué papelón!”.

In 1912 he started to record for Columbia. His success was so great that the word “Pacho” became a synonym of “recordings”.

Read also:

- History of Tango – Part 1

- History of Tango – Part 2

- History of Tango – Part 3

- History of Tango – Part 4

Bibliography:

-

- “Crónica general del tango”, José Gobello, Editorial Fraterna, 1980.

- “El tango”, Horacio Salas, Editorial Aguilar, 1996.

- “Historia del tango – La Guardia Vieja”, Rubén Pesce, Oscar del Priore, Silvestre Byron, Editorial Corregidor 1977.

- “El tango, el gaucho y Buenos Aires”, Carlos Troncaro, Editorial Argenta, 2009.

- “El tango, el bandoneón y sus intérpretes”, Oscar Zucchi, Ediciones Corregidor, 1998.

- https://www.todotango.com/english/

If you are in the San Francisco Bay Area and want to learn to dance Tango, you can:

Enrique Saborido, with the beautiful Lola Candales, Uruguayan as he and his muse, come tango dancers. In 1908, with the growing popularity of tango, he opens academia in Cerrito 1070, which they managed until 1912. In that year he decided to go to Paris with other tango personalities. There, he taught to dance tango to the European aristocracy and show off as a professional dancer at the Savoy and the Royal Theatre in London. He referred to other good dancers: Jorge Newbery (one of the first Latin American aircraft pilots. He was also an engineer, and is considered to be the architect and founder of the Argentine Air Force), his close friend Alberto J. Mascías, Alberto Lange, and Martin Edmund Hileret Anchorena.

Enrique Saborido, with the beautiful Lola Candales, Uruguayan as he and his muse, come tango dancers. In 1908, with the growing popularity of tango, he opens academia in Cerrito 1070, which they managed until 1912. In that year he decided to go to Paris with other tango personalities. There, he taught to dance tango to the European aristocracy and show off as a professional dancer at the Savoy and the Royal Theatre in London. He referred to other good dancers: Jorge Newbery (one of the first Latin American aircraft pilots. He was also an engineer, and is considered to be the architect and founder of the Argentine Air Force), his close friend Alberto J. Mascías, Alberto Lange, and Martin Edmund Hileret Anchorena. Mamita, as Luis Teisseire told, “was tall, skinny, authoritarian. Of dark complexion, rather ‘achinada’, brave, black eyes. Always she wore a long, dark silk suit. She looked all covered with a high collar. At her house, among her women, she had la Ñata Rosaura, Herminia and Joaquina. After a glass door, it was a long courtyard with the rooms on the side and the classic dining room. ” There, played the piano Sergio Mendizabal, El Gordo Mauricio and Teisseire, our informant.

Mamita, as Luis Teisseire told, “was tall, skinny, authoritarian. Of dark complexion, rather ‘achinada’, brave, black eyes. Always she wore a long, dark silk suit. She looked all covered with a high collar. At her house, among her women, she had la Ñata Rosaura, Herminia and Joaquina. After a glass door, it was a long courtyard with the rooms on the side and the classic dining room. ” There, played the piano Sergio Mendizabal, El Gordo Mauricio and Teisseire, our informant. Carmen Gomez has been born around 1830 and began dancing at the Academia de Pardos y Morenos, located on Calle del Parque (current Lavalle). Around the 1854s she opened what became known as the “Academia de la Parda Gomez”, in the vicinity of the Plaza Lorea (part of the current Plaza del Congreso). After selling it, in 1864, she opened another in Corrientes 437.

Carmen Gomez has been born around 1830 and began dancing at the Academia de Pardos y Morenos, located on Calle del Parque (current Lavalle). Around the 1854s she opened what became known as the “Academia de la Parda Gomez”, in the vicinity of the Plaza Lorea (part of the current Plaza del Congreso). After selling it, in 1864, she opened another in Corrientes 437. Luciana Acosta,”La Moreyra”, was a popular dancer of the neighborhood of San Cristobal. She was a source of inspiration in the literary field: Jose Sebastian Tallón portrayed her in his book “Tango in the stages of forbidden music” (Buenos Aires, 1959); and Juan Carlos Ghiano makes her protagonist of his play “La Moreyra,” released by the company Tita Merello in 1962. There is a film version starring the same actress.

Luciana Acosta,”La Moreyra”, was a popular dancer of the neighborhood of San Cristobal. She was a source of inspiration in the literary field: Jose Sebastian Tallón portrayed her in his book “Tango in the stages of forbidden music” (Buenos Aires, 1959); and Juan Carlos Ghiano makes her protagonist of his play “La Moreyra,” released by the company Tita Merello in 1962. There is a film version starring the same actress. Joaquina Marán, “La China Joaquina”, a wonderful tango dancer, was the favorite at “lo de Mamita”, and later herself the manager of dance houses in the first decade of the 19th century. Tall, not pretty but very interesting and seductive brunette, of very pleasant conversation, Juan Bergamino dedicated to her his tango

Joaquina Marán, “La China Joaquina”, a wonderful tango dancer, was the favorite at “lo de Mamita”, and later herself the manager of dance houses in the first decade of the 19th century. Tall, not pretty but very interesting and seductive brunette, of very pleasant conversation, Juan Bergamino dedicated to her his tango  Margarita Verdier, or Verdiet, whom some called “La Oriental “and “La Rubia Mireya”, resident of the neighborhood of Almagro, Castro Barros 433. Daughter of French parents born in Uruguay, had a reputation for “night owl”, given to the “dance of the compadritos”, as tango was stigmatized by then. She was immortalized by Manuel Romero and Francisco Canaro in the tango

Margarita Verdier, or Verdiet, whom some called “La Oriental “and “La Rubia Mireya”, resident of the neighborhood of Almagro, Castro Barros 433. Daughter of French parents born in Uruguay, had a reputation for “night owl”, given to the “dance of the compadritos”, as tango was stigmatized by then. She was immortalized by Manuel Romero and Francisco Canaro in the tango  Elías Alippi, tango dancer, actor, and theater and film director, playwright of comedies and sainetes (1883-1942). He debuted on the scene in 1904 dancing a tango with Anita Posed in “Justicia criolla”, zarzuela by Ezequiel Soria, music of Antonio Reynoso, who that season replied the company of Jerónimo Podestá. He was also one of the best dancers of the local “María la Vasca” and other nightspots of that time, as well as on stage. He danced for the last time in the film

Elías Alippi, tango dancer, actor, and theater and film director, playwright of comedies and sainetes (1883-1942). He debuted on the scene in 1904 dancing a tango with Anita Posed in “Justicia criolla”, zarzuela by Ezequiel Soria, music of Antonio Reynoso, who that season replied the company of Jerónimo Podestá. He was also one of the best dancers of the local “María la Vasca” and other nightspots of that time, as well as on stage. He danced for the last time in the film  Francisco Ducasse, one of his dancing partners was named Mimí Pinsonette. He was married to the actress Angelina Pagano. He used to frequent «lo de Hansen». Francisco García Jiménez says that the very charming princess de Murat was intertwined with the tango skill of the fine handsome young man of Buenos Aires, on tour in Paris, in a tango competition organized by the journal Excelsior at the Fémina theater on the avenue of the Champs-Elysées. Obviously, they were awarded the first prize. He was born and died in Buenos Aires.

Francisco Ducasse, one of his dancing partners was named Mimí Pinsonette. He was married to the actress Angelina Pagano. He used to frequent «lo de Hansen». Francisco García Jiménez says that the very charming princess de Murat was intertwined with the tango skill of the fine handsome young man of Buenos Aires, on tour in Paris, in a tango competition organized by the journal Excelsior at the Fémina theater on the avenue of the Champs-Elysées. Obviously, they were awarded the first prize. He was born and died in Buenos Aires. La Parda Flora was very well known by 1880, so much that she is mentioned in “Milonga de Tancredi” (“The other night at Tancredi / I danced with Boladora / was the Brown and Flora; / what he saw me, he estriló”). She showed up her art in La Pandora of La Boca, in peringundines of Corrientes, and had its own academia in 25 de Mayo and Viamonte, to spend her final years in Flores. It is also remembered in the milonga

La Parda Flora was very well known by 1880, so much that she is mentioned in “Milonga de Tancredi” (“The other night at Tancredi / I danced with Boladora / was the Brown and Flora; / what he saw me, he estriló”). She showed up her art in La Pandora of La Boca, in peringundines of Corrientes, and had its own academia in 25 de Mayo and Viamonte, to spend her final years in Flores. It is also remembered in the milonga  La Gaucha Manuela, referred by Roberto Firpo in an interview with Dr. Benarós: “I started playing the piano at the Velodrome, in 1907, with Bevilacqua. Then I was twenty years old and came from the Corrales, of Rioja and Caseros. The owner of The Velodrome was Pesce, I believe the father of who was later the owner of Luna Park. The place occupied an area of about four blocks. In the center was a mound of dirt. Inside, a track, used by cyclists. To get there you needed to go through a dirt road, which sometimes became mud. It was two blocks from Hansen. Drinks were served on tables placed under the trees. It had rooms, also. From The Velodrome, you could see when music was playing in lo de Hansen. The Gaucha Manuela was a regular there and was the kept woman of a rich young man called Del Carril, which I believe expended on her four or five million. She was brunette, very pretty, and very ‘criolla’ when speaking. She was a wonderful dancer, capable of grabbing a knife and start with the blows. I dedicated a tango

La Gaucha Manuela, referred by Roberto Firpo in an interview with Dr. Benarós: “I started playing the piano at the Velodrome, in 1907, with Bevilacqua. Then I was twenty years old and came from the Corrales, of Rioja and Caseros. The owner of The Velodrome was Pesce, I believe the father of who was later the owner of Luna Park. The place occupied an area of about four blocks. In the center was a mound of dirt. Inside, a track, used by cyclists. To get there you needed to go through a dirt road, which sometimes became mud. It was two blocks from Hansen. Drinks were served on tables placed under the trees. It had rooms, also. From The Velodrome, you could see when music was playing in lo de Hansen. The Gaucha Manuela was a regular there and was the kept woman of a rich young man called Del Carril, which I believe expended on her four or five million. She was brunette, very pretty, and very ‘criolla’ when speaking. She was a wonderful dancer, capable of grabbing a knife and start with the blows. I dedicated a tango  Juana Rebenque, referred by Juan Santa Cruz -brother of the author of

Juana Rebenque, referred by Juan Santa Cruz -brother of the author of  Filiberto, Juan “Mascarilla”, father musician and composer Juan de Dios Filiberto. Eminent tango dancer of the first period; natural and spontaneous creator. Owner or administrator “Bailetín El Palomar”, then the “Tancredi” (c. 1882), nearby recreational Suarez and Necochea, in the heart of La Boca. We quote from an interview by ‘La Canción Porteña’ (Buenos Aires, 1963) in which his son tells us: “‘My father was cheerful, a bit careless of all things, but simple and good, had an easy laugh and good sense of humor in his eyes and always good jokes escaping from his mouth. He sang in a nice tenor voice, which I liked to listen to. Dancer by nature, of the best tango dancers of La Boca; his reputation was well recognized. According to his character, he worked on the most different and contradictory jobs, from the owner of dance halls to sailor, wrestler, or construction worker. He was a friend and often also the bodyguard of Pepe Fernandez, strongman, and leader of La Boca, which was the first supporter of Mitre and then of General Roca. He possessed extraordinary power, often acting in the circus Rafetto wrestling and weight lifter.”

Filiberto, Juan “Mascarilla”, father musician and composer Juan de Dios Filiberto. Eminent tango dancer of the first period; natural and spontaneous creator. Owner or administrator “Bailetín El Palomar”, then the “Tancredi” (c. 1882), nearby recreational Suarez and Necochea, in the heart of La Boca. We quote from an interview by ‘La Canción Porteña’ (Buenos Aires, 1963) in which his son tells us: “‘My father was cheerful, a bit careless of all things, but simple and good, had an easy laugh and good sense of humor in his eyes and always good jokes escaping from his mouth. He sang in a nice tenor voice, which I liked to listen to. Dancer by nature, of the best tango dancers of La Boca; his reputation was well recognized. According to his character, he worked on the most different and contradictory jobs, from the owner of dance halls to sailor, wrestler, or construction worker. He was a friend and often also the bodyguard of Pepe Fernandez, strongman, and leader of La Boca, which was the first supporter of Mitre and then of General Roca. He possessed extraordinary power, often acting in the circus Rafetto wrestling and weight lifter.” Arturo De Nava, composer, singer pre-gradeliano. Was born apparently in Paysandú in 1876 and died in Buenos Aires, where he had settled since his youth, on October 22, 1932 …. Initially, a natural dancer with great style, he was the first one to earn fame on the stage, prior to Ain and Alippi, dancing tangos in plays since 1903 in the Podestá troupe. He was very handsome. Because of his appearance, unmistakable, his photographs appear illustrating several editions of the popular magazine Caras y Caretas of Buenos Aires, in 1903. ”

Arturo De Nava, composer, singer pre-gradeliano. Was born apparently in Paysandú in 1876 and died in Buenos Aires, where he had settled since his youth, on October 22, 1932 …. Initially, a natural dancer with great style, he was the first one to earn fame on the stage, prior to Ain and Alippi, dancing tangos in plays since 1903 in the Podestá troupe. He was very handsome. Because of his appearance, unmistakable, his photographs appear illustrating several editions of the popular magazine Caras y Caretas of Buenos Aires, in 1903. ” Pedrín “La Vieja”. Domingo Greco says in his memoirs: “Then came a certain Pedrín, that was my classmate: we nicknamed him ‘La Vieja (The Old Lady)”. He used to live at Chile street, between Tacuarí and Piedras. He brought tango to its maximum refinement. Even before 1900, he was the best dancer known. He had a lot of initiative. He was elegant, very musical, and with an amazing speed in his legs. In a word, he was the best of all time. Benito Bianquet “El Cachafaz” emerged as his only imitator.”

Pedrín “La Vieja”. Domingo Greco says in his memoirs: “Then came a certain Pedrín, that was my classmate: we nicknamed him ‘La Vieja (The Old Lady)”. He used to live at Chile street, between Tacuarí and Piedras. He brought tango to its maximum refinement. Even before 1900, he was the best dancer known. He had a lot of initiative. He was elegant, very musical, and with an amazing speed in his legs. In a word, he was the best of all time. Benito Bianquet “El Cachafaz” emerged as his only imitator.” I have been asking myself why dancers often have a reputation for being sexual, feisty, rebellious, irreverent, marginal, indifferent to what people say about them, but also elegant, tough, self-reliant, respectable, admired…?

I have been asking myself why dancers often have a reputation for being sexual, feisty, rebellious, irreverent, marginal, indifferent to what people say about them, but also elegant, tough, self-reliant, respectable, admired…? On the other hand, all negative qualifications attached to dancers come not from other GOOD DANCERS, but from those who are not. It is perhaps a form of revenge from the ones whose value resides in being useful to society -a laudable situation- against those whose major contribution is an uninterested and useless beauty that can’t be sold in the markets.

On the other hand, all negative qualifications attached to dancers come not from other GOOD DANCERS, but from those who are not. It is perhaps a form of revenge from the ones whose value resides in being useful to society -a laudable situation- against those whose major contribution is an uninterested and useless beauty that can’t be sold in the markets.

Between 1860 and 1915, Buenos Aires experienced exponential growth.

Between 1860 and 1915, Buenos Aires experienced exponential growth. The following year, in 1898,

The following year, in 1898,  Enrique Santos Discépolo’s father, José Luis Roncallo (who was presumably the one that first suggested tango music for them), and Ángel Villoldo (who probably wrote

Enrique Santos Discépolo’s father, José Luis Roncallo (who was presumably the one that first suggested tango music for them), and Ángel Villoldo (who probably wrote  Ángel Villoldo (1861-1919) is considered by many “El padre del Tango” (The father of Tango) and unanimously considered the most representative artist of the Guardia Vieja. Little is known about his childhood, and the information about his youth is often contradictory. From an interview made with him by the newspaper “La Razón” in 1917, we know that he was “cuarteador” [1] of “La Calle Larga” (The Long Street, today’s Montes de Oca) at the time that his interest in music appears, and that he sung and played guitar and harmonica.

Ángel Villoldo (1861-1919) is considered by many “El padre del Tango” (The father of Tango) and unanimously considered the most representative artist of the Guardia Vieja. Little is known about his childhood, and the information about his youth is often contradictory. From an interview made with him by the newspaper “La Razón” in 1917, we know that he was “cuarteador” [1] of “La Calle Larga” (The Long Street, today’s Montes de Oca) at the time that his interest in music appears, and that he sung and played guitar and harmonica.

His rise to fame came in 1903 when the singer Dorita Miramar sang

His rise to fame came in 1903 when the singer Dorita Miramar sang  On Christmas day in 1905, Villoldo wakes up at 7 am by Enrique Saborido, who was up all night writing a song and needed a lyric. He knew that Villoldo was fast, that he could improvise verses as a payador. The night before, on Christmas Eve, Saborido was mocked by his friends for paying too much attention to the Uruguayan singer Lola Candles. So they challenged him to write a song for her. He took the challenge and promised to have the song ready to be sung by Lola the next day. At 10 am, they presented to Lola

On Christmas day in 1905, Villoldo wakes up at 7 am by Enrique Saborido, who was up all night writing a song and needed a lyric. He knew that Villoldo was fast, that he could improvise verses as a payador. The night before, on Christmas Eve, Saborido was mocked by his friends for paying too much attention to the Uruguayan singer Lola Candles. So they challenged him to write a song for her. He took the challenge and promised to have the song ready to be sung by Lola the next day. At 10 am, they presented to Lola

In 1907 he was sent by the department store Gath y Chaves, the most successful in Buenos Aires then, to make some of the first tangos and Argentine music recordings to Paris with

In 1907 he was sent by the department store Gath y Chaves, the most successful in Buenos Aires then, to make some of the first tangos and Argentine music recordings to Paris with  On November 8, 1887, Emile Berliner, a German immigrant working in Washington, D.C., patented a successful sound recording system. Berliner was the first inventor to stop recording on cylinders and start recording on flat disks. The first records were made of glass, zinc, and plastic. A spiral groove with the sound information was etched into the flat record. Next, the record was rotated on the gramophone. The “arm” of the gramophone held a needle that read the grooves in the record by vibration and transmitting the information to the gramophone speaker. Berliner’s disks (records) were the first sound recordings that could be mass-produced by creating master recordings from which molds were made.

On November 8, 1887, Emile Berliner, a German immigrant working in Washington, D.C., patented a successful sound recording system. Berliner was the first inventor to stop recording on cylinders and start recording on flat disks. The first records were made of glass, zinc, and plastic. A spiral groove with the sound information was etched into the flat record. Next, the record was rotated on the gramophone. The “arm” of the gramophone held a needle that read the grooves in the record by vibration and transmitting the information to the gramophone speaker. Berliner’s disks (records) were the first sound recordings that could be mass-produced by creating master recordings from which molds were made.

The first Argentinean Presidents promoted the immigration of the European workforce, defeated the indigenous people who had still claimed part of the Argentine territory, favored an economic model of production and export of agricultural goods following British-led ideas of the international division of work, and invested in the technology and infrastructure that made possible such model. A modern port was constructed in Puerto Madero, and a railroad network transported the whole production of the entire country to this port. Buenos Aires greatly benefitted from these changes and grew exponentially. Between 1871 and 1915, Argentina received 5 million immigrants, mostly Europeans. Almost all of them stayed in Buenos Aires.

The first Argentinean Presidents promoted the immigration of the European workforce, defeated the indigenous people who had still claimed part of the Argentine territory, favored an economic model of production and export of agricultural goods following British-led ideas of the international division of work, and invested in the technology and infrastructure that made possible such model. A modern port was constructed in Puerto Madero, and a railroad network transported the whole production of the entire country to this port. Buenos Aires greatly benefitted from these changes and grew exponentially. Between 1871 and 1915, Argentina received 5 million immigrants, mostly Europeans. Almost all of them stayed in Buenos Aires. All these new arrivals to Buenos Aires had few resources and were very poor. They could only afford housing in the poorest neighborhoods, where the Afro-Argentineans, descendants of the African slaves, had been populating since 1813’s abolition of slavery. They were the locals. If any newcomer wanted to know something about Buenos Aires, they had to ask the Afro-Argentineans, who, before this massive immigration, constituted one-third of the population.

All these new arrivals to Buenos Aires had few resources and were very poor. They could only afford housing in the poorest neighborhoods, where the Afro-Argentineans, descendants of the African slaves, had been populating since 1813’s abolition of slavery. They were the locals. If any newcomer wanted to know something about Buenos Aires, they had to ask the Afro-Argentineans, who, before this massive immigration, constituted one-third of the population. Between 1820 and 1850, before the Argentine Constitution was written and immigration was promoted, Argentina was under the administration of Juan Manuel de Rosas. During this time, the Afro-Argentineans enjoyed a period of greater participation and freedom of expression. Rosas was a landowner in the province of Buenos Aires with a perfect resume. When he was only thirteen, he fought heroically against the English invasions. Later on, he proved to be a very efficient administrator of cattle ranches and a successful businessman. Rosas created, financed, and trained his militia of gauchos, which would go on to be integrated into the state as an official regiment. They soon earned a reputation for being highly disciplined, and Rosas was able to establish order at the border with the indigenous populations. In 1819, Rosas put this militia at the province’s governor’s service to quell an uprising against him. This is how Rosas became known as “El Restaurador de las Leyes” (”The Restorer of Law’).

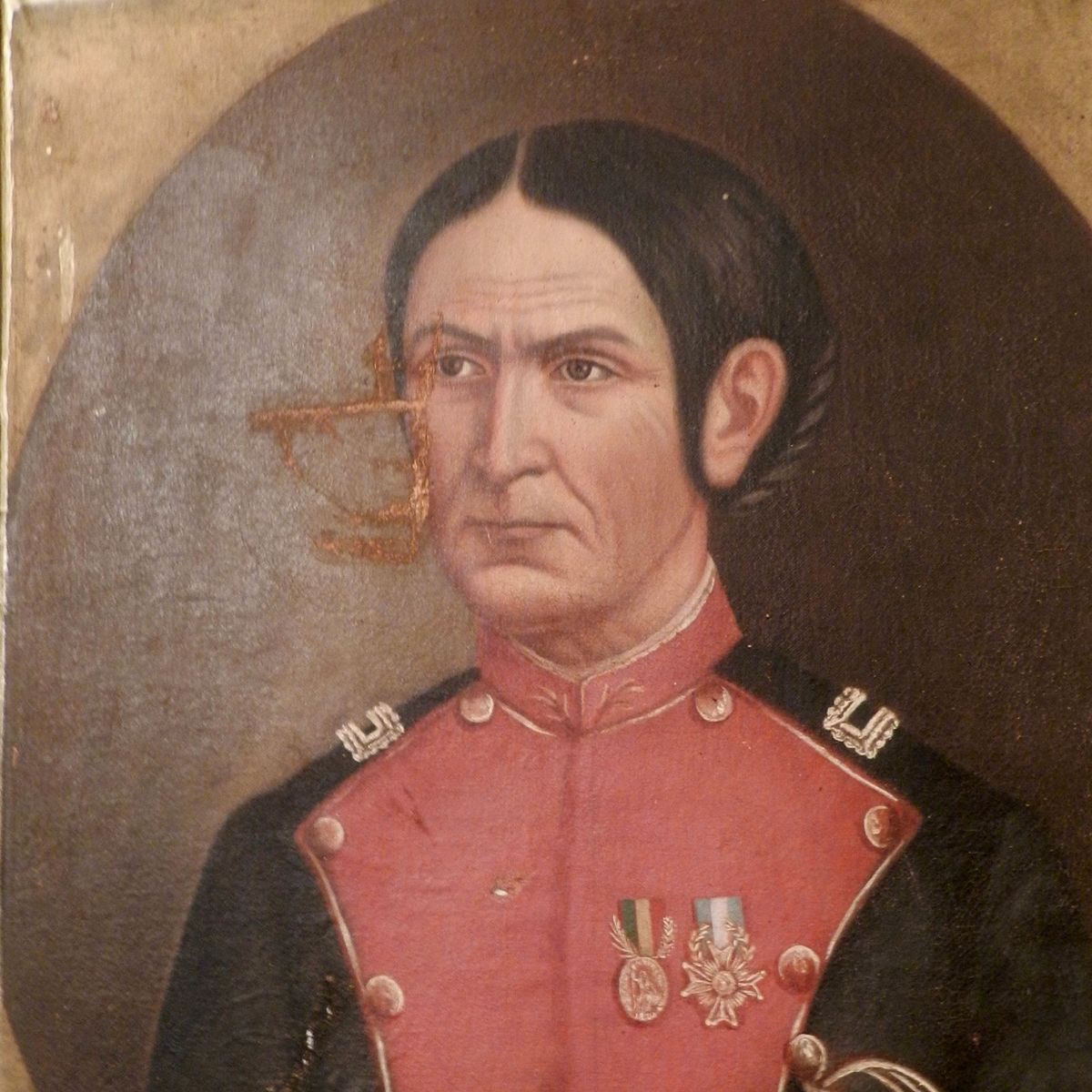

Between 1820 and 1850, before the Argentine Constitution was written and immigration was promoted, Argentina was under the administration of Juan Manuel de Rosas. During this time, the Afro-Argentineans enjoyed a period of greater participation and freedom of expression. Rosas was a landowner in the province of Buenos Aires with a perfect resume. When he was only thirteen, he fought heroically against the English invasions. Later on, he proved to be a very efficient administrator of cattle ranches and a successful businessman. Rosas created, financed, and trained his militia of gauchos, which would go on to be integrated into the state as an official regiment. They soon earned a reputation for being highly disciplined, and Rosas was able to establish order at the border with the indigenous populations. In 1819, Rosas put this militia at the province’s governor’s service to quell an uprising against him. This is how Rosas became known as “El Restaurador de las Leyes” (”The Restorer of Law’). He became the Governor of the province of Buenos Aires and, between 1835 and 1852, was the prominent leader of the Argentinean Confederation. This period of Argentina’s history is called the “Era of Rosas.” He obtained the necessary support for his administration from the poorer sectors of the population of the City of Buenos Aires (integrated for a majority of Afro-Argentineans), and the gauchos of the countryside close to the City (many of whom were also Afro-Argentinean.) During his tenure, Rosas attended the “candombes” (celebrations) of the Afro-Argentineans as an honored guest. Also, during this period, the carnivals began in Buenos Aires.

He became the Governor of the province of Buenos Aires and, between 1835 and 1852, was the prominent leader of the Argentinean Confederation. This period of Argentina’s history is called the “Era of Rosas.” He obtained the necessary support for his administration from the poorer sectors of the population of the City of Buenos Aires (integrated for a majority of Afro-Argentineans), and the gauchos of the countryside close to the City (many of whom were also Afro-Argentinean.) During his tenure, Rosas attended the “candombes” (celebrations) of the Afro-Argentineans as an honored guest. Also, during this period, the carnivals began in Buenos Aires. In the origins of social dances, we observe no physical contact between partners; then they take each other hands, developing the “minuet” during the 1600s, which led to dancing in each other’s arms, with the “waltz” in the 1700s. The direction of the evolution of social partner dancing becomes evident: a closing of the distance between the partners that culminates in the embrace of Tango.

In the origins of social dances, we observe no physical contact between partners; then they take each other hands, developing the “minuet” during the 1600s, which led to dancing in each other’s arms, with the “waltz” in the 1700s. The direction of the evolution of social partner dancing becomes evident: a closing of the distance between the partners that culminates in the embrace of Tango. This technique soon became the characteristic dance of the poorest inhabitants of Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Rosario, and the villages located south of Buenos Aires in an area known as “Barracas al sur”, Avellaneda, and Sarandí.

This technique soon became the characteristic dance of the poorest inhabitants of Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Rosario, and the villages located south of Buenos Aires in an area known as “Barracas al sur”, Avellaneda, and Sarandí. The Andalusian-style houses of the Southern side of Buenos Aires, San Telmo, and La Boca were soon creatively transformed into rooms to rent.

The Andalusian-style houses of the Southern side of Buenos Aires, San Telmo, and La Boca were soon creatively transformed into rooms to rent. In 1871, Buenos Aires suffered a yellow fever epidemic that killed 8% of its population, most living in these houses. The situation was so dire (with more than 13,000 people dying in 4 months) that it was necessary to open a new cemetery in the area of La Chacarita.

In 1871, Buenos Aires suffered a yellow fever epidemic that killed 8% of its population, most living in these houses. The situation was so dire (with more than 13,000 people dying in 4 months) that it was necessary to open a new cemetery in the area of La Chacarita. The first Andalusian tango to reach mass popularity was composed in Argentina in 1874. The title is

The first Andalusian tango to reach mass popularity was composed in Argentina in 1874. The title is  In those years, the “organito,” a portable player, had a significant role in the initial spread of the Tango. It was made of tubes or flutes and a keyboard operated by the cylinder, enabling the passage of air to produce different notes. Bellows generate air activated simultaneously with the cylinder by rotating a handle. The “organito,” like the organ and the bandoneón, is a wind instrument. It is essential to differentiate the “organito” from the “organillo,” which is more common in Spain and produces sound from strings. The sound of the “organito” prepared the ears of the Porteños for a natural transition to the bandoneón in Tango when it finally arrived in 1880.

In those years, the “organito,” a portable player, had a significant role in the initial spread of the Tango. It was made of tubes or flutes and a keyboard operated by the cylinder, enabling the passage of air to produce different notes. Bellows generate air activated simultaneously with the cylinder by rotating a handle. The “organito,” like the organ and the bandoneón, is a wind instrument. It is essential to differentiate the “organito” from the “organillo,” which is more common in Spain and produces sound from strings. The sound of the “organito” prepared the ears of the Porteños for a natural transition to the bandoneón in Tango when it finally arrived in 1880.

During that time, Spain allowed its colonies to only trade with Spain and other Spanish colonies. To avoid ships being captured by enemy nations and pirates, Spain established a unique route to transit goods between the settlements and Spain. Unfortunately, this route was not favorable to Buenos Aires, making goods too expensive and scarce to the inhabitants of Rio de la Plata. Consequently, smuggling became the only profitable business for its population and the only way to acquire what it needed to survive.

During that time, Spain allowed its colonies to only trade with Spain and other Spanish colonies. To avoid ships being captured by enemy nations and pirates, Spain established a unique route to transit goods between the settlements and Spain. Unfortunately, this route was not favorable to Buenos Aires, making goods too expensive and scarce to the inhabitants of Rio de la Plata. Consequently, smuggling became the only profitable business for its population and the only way to acquire what it needed to survive.

Another origin of gauchos came from the Jesuit Missions after they were dismantled in the area now known as the border between Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay, populated mainly by natives of the Guaraní nations. These missions were efficiently organized and very productive. For that reason, the missions attracted the attention of the powers of the time, who were suspicious of their prosperity.

Another origin of gauchos came from the Jesuit Missions after they were dismantled in the area now known as the border between Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay, populated mainly by natives of the Guaraní nations. These missions were efficiently organized and very productive. For that reason, the missions attracted the attention of the powers of the time, who were suspicious of their prosperity. The “facón” was not only a weapon but also an indispensable everyday tool, as well as the “rebenque” and the “poncho”.

The “facón” was not only a weapon but also an indispensable everyday tool, as well as the “rebenque” and the “poncho”. The gauchos were horseback riders by nature. In their childhoods, they learned to ride horses at the same time; they learned how to walk. Similarly to the cattle that the Spanish brought, the horses brought over from Spain reproduced very quickly, providing the gauchos with a large pool of horses to use and trade. They call their horses “pingo” and “flete.”

The gauchos were horseback riders by nature. In their childhoods, they learned to ride horses at the same time; they learned how to walk. Similarly to the cattle that the Spanish brought, the horses brought over from Spain reproduced very quickly, providing the gauchos with a large pool of horses to use and trade. They call their horses “pingo” and “flete.” The gaucho’s favorite musical instrument was the guitar (”guitarra criolla”), inherited from Spain (guitarra española.) The poetry of the gauchos accompanied by a guitar is called “payada”, and the performer “payador.”

The gaucho’s favorite musical instrument was the guitar (”guitarra criolla”), inherited from Spain (guitarra española.) The poetry of the gauchos accompanied by a guitar is called “payada”, and the performer “payador.”

An example of the ideals of women can be seen in the life of Juana Azurduy de Padilla (1780-1860).

An example of the ideals of women can be seen in the life of Juana Azurduy de Padilla (1780-1860).